I met Dr. Lloyd Johnson at the Northwest Christian Writers Association Renewal conference in May. We discovered a mutual interest in Middle East issues, though with different emphases.

Following are excerpts from the bio on Dr. Johnson’s blog http://lloydjohnson.org/

“Following the man of Galilee, and learning from Jesus’ stories, I began to write tales about people struggling with the issues in their lives and the current conflicts in that part of the world. We in the United States learn of the Arab Spring but have little information about ordinary people’s daily lives in Israel and the West Bank.

Previously, as Clinical Professor of Surgery at the University of Washington, I taught and practiced general and thoracic surgery in Seattle for many years . . . . Additionally I worked as Professor of Surgery at the Haile Selassie I University in Gondar, Ethiopia for three years. I served for two years in the U.S. Air Force as a flight surgeon, and volunteered in hospitals for several weeks each in Kenya, India, and in Pakistan with Afghan refugees.”

Here is one of Dr. Johnson’s entries, posted on June 16, 2012

“THOSE WHO CANNOT REMEMBER THE PAST ARE CONDEMNED TO REPEAT IT.”

from George Santayana (1863 – 1952), The Life of Reason, Volume 1, 1905

Memory is a gift. When you wake up in the morning, you may still remember what happened yesterday—or 20 years ago. Sleep does not erase it. Like memory in your computer, it should still be there on re-start. You need the anchor of memory to know who you are and how you relate to the rest of the world around you.

Santayana addressed long term recollections of history, ours or others, that are crucial to teach us how to live in the present. We can choose to learn from the past or not. Both the good and the bad events. Father’s Day brings inspiring memories to me. Many are not so fortunate to have had a loving dad. But at age 18 I lost him tragically, to a drunk driver. Devastated, I learned to forgive and not live in bitterness. The past is history, only to inform the present, not paralyze it.

Paul, the famous Jewish apostle, wrote to his friends in Philippi, “Forgetting what is behind, and straining toward what is ahead, I press on…” He had much to forget—persecution to death of Jesus followers, and then becoming one himself, his own beatings, shipwrecks, imprisonments and finally execution. He determined to not let the past poison his life, or that of others.

“Never again” is the appropriate slogan for remembering the Holocaust. But how do its survivors and their descendants deal with those memories? Perhaps some do forget. Others forgive and move on. But dwelling on the tragedy seems to fuel Zionism’s fires to burn others. Quoting from Jewish writer, Mark Braverman:

“Never again” is the appropriate slogan for remembering the Holocaust. But how do its survivors and their descendants deal with those memories? Perhaps some do forget. Others forgive and move on. But dwelling on the tragedy seems to fuel Zionism’s fires to burn others. Quoting from Jewish writer, Mark Braverman:

“…Israeli writer Avraham Burg sees the Holocaust as the central reality for Israel—infecting every aspect of daily life and even driving government policy:

‘In our eyes, we are still partisan fighters, ghetto rebels, shadows in the camps, no matter the nation, state, armed forces, gross domestic product, or international standing. The Shoah is our life, and we will not forget it and we will not let anyone forget us. We have pulled the Shoah out of its historic context and turned it into a plea and a generator for every deed. All is compared to the Shoah, dwarfed by the Shoah, and therefore all is allowed—be it fences, sieges,…curfews, food and water deprivation, or unexplained killings…Everything seems dangerous to us…(2008, 78′” Braveman’s page 87

“Our world-view—our attitude toward the other—is so totally conditioned by our sense of our entitlement, undergirded by the idée fixe of our eternal victimhood, that we cannot see the other except as a threat that must be neutralized.” Braverman’s “Fatal Embrace,” page 93.

Does a historic ethnic abuse seven decades ago justify another now, the oppressed becoming the oppressors?

“Never again” is the appropriate slogan for remembering the Holocaust. But how do its survivors and their descendants deal with those memories? Perhaps some do forget. Others forgive and move on. But dwelling on the tragedy seems to fuel Zionism’s fires to burn others. Quoting from Jewish writer, Mark Braverman:

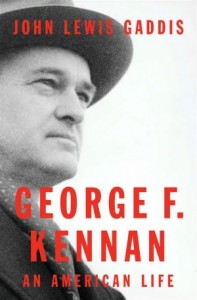

“Never again” is the appropriate slogan for remembering the Holocaust. But how do its survivors and their descendants deal with those memories? Perhaps some do forget. Others forgive and move on. But dwelling on the tragedy seems to fuel Zionism’s fires to burn others. Quoting from Jewish writer, Mark Braverman: American citizens built bomb shelters and wondered if their children would have a future. Christians feared the Soviet Union’s embrace of atheism.

American citizens built bomb shelters and wondered if their children would have a future. Christians feared the Soviet Union’s embrace of atheism. The book, which won the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for biography, brings alive those times of fear bordering on hysteria. It hints of policies which might serve us in our current conflict.

The book, which won the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for biography, brings alive those times of fear bordering on hysteria. It hints of policies which might serve us in our current conflict. In those earlier times, the U.S. was accused of supporting dictatorial regimes in certain African and South American countries because the regimes touted themselves as anti-communist. Now the U.S. is accused of propping up former dictators like Ben Ali in Tunisia and Mubarak in Egypt. These men clamped down on the growth of Islamists in their countries, so we supported them even if they employed brutal methods. Egypt, especially, became a huge recipient of U.S. aid.

In those earlier times, the U.S. was accused of supporting dictatorial regimes in certain African and South American countries because the regimes touted themselves as anti-communist. Now the U.S. is accused of propping up former dictators like Ben Ali in Tunisia and Mubarak in Egypt. These men clamped down on the growth of Islamists in their countries, so we supported them even if they employed brutal methods. Egypt, especially, became a huge recipient of U.S. aid. Ozzie appears to have died because someone pierced him with an arrow.

Ozzie appears to have died because someone pierced him with an arrow. Christian history fascinates: all the advances and retreats, deaths and resurrections of the church over the centuries. Such understanding allows perspective in these times of waning Christian influence in the old countries of “Christendom.”

Christian history fascinates: all the advances and retreats, deaths and resurrections of the church over the centuries. Such understanding allows perspective in these times of waning Christian influence in the old countries of “Christendom.”