This year, the electricity stayed on. The forecast remains stuck in rain mode rather than snow. A few years ago, it snowed, and the power was off for days before our advent concert. We came anyway and huddled together in our winter coats and blankets, listening to a program powered by a generator. Regardless, the blessings are the same, the songs are heard and absorbed. The old story, is as precious as ever in a still-dark world, where innocents cannot be protected.

Our end of the island, about an hour north of Seattle by ferry, is home to around 15,000 citizens. Older islanders have been here for generations, farming, logging, and fishing. Newcomers join, desiring a slower pace. The island ambience attracts artists, who stay full-time or part-time between work in other places. Writers, sculptors, painters, dancers, musicians, dramatists, and others ply their craft.

The holiday season calls on much of this artistic talent, creating so many gatherings and performances that one has difficulty attending all of them. For our church’s advent concert this year, we knew to come early, for seats filled up quickly with islanders, not all from the church. We hardly breathed during the performance of musicians and readers. Where did all this talent come from? How blessed we are.

We know we are blessed. We have our computers, iPhones, iPads, Kindles, and Nooks, but they work only as long as we have electricity. We marvel at another blessing that our country struggles to keep—that of community.

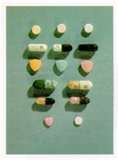

Few of us look forward to dental visits. Nevertheless, dental work today is less dreaded because of modern analgesics which numb the gum and allow repairs to be done in relative painlessness, compared to a generation or so ago. Indeed we become so used to the miracles of modern medical science that we tend to think all our physical ills should be resolved with a shot or a pill.

Few of us look forward to dental visits. Nevertheless, dental work today is less dreaded because of modern analgesics which numb the gum and allow repairs to be done in relative painlessness, compared to a generation or so ago. Indeed we become so used to the miracles of modern medical science that we tend to think all our physical ills should be resolved with a shot or a pill.