In a recent speech, William J. Burns, Deputy Secretary for the U.S. State Department, said: “The Middle East is a place where pessimists seldom lack for either company or validation, where skeptics hardly ever seem wrong. It is a place where American policymakers often learn humility the hard way.”

As Burns pointed out, the recent revolutions in that part of the world have unloosed ancient hatreds and ethnic conflicts, most tragically evident in Syria.

Should we wash our hands of the Middle East and turn our backs on it as we become less dependent on it for our energy supplies?

No, Burns said. The region “has a nasty way of reminding us of its relevance.” Much of the global economy still depends on its large reserves of oil. Extremism, once released from there, cannot be forced back into the bottle. Syria has chemical weapons, and Iran threatens to produce nuclear ones. Three major religions of the world worship at its sacred places.

Burns says we are far better off “working persistently to help shape events, rather than wait for them to be shaped for us.”

What can ordinary Americans do? Connect with the reconcilers. Dr. Lloyd Johnson, a Christian, has established dialogs with several individuals and groups in Israel/Palestine. Other groups, religious and secular, seek reconciliation between the different parties.

Develop respect and empathy for the diverse Middle East peoples, even those with whom you don’t agree. They are mothers, fathers, sons, daughters. They have fears and dreams. Some spew hatred, but others, in all the ethnic groups, work courageously for reconciliation. Connect with them.

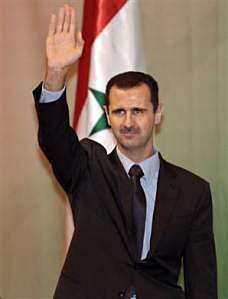

The war in Syria is a conundrum, a problem that appears to have no favorable resolution. The opposition, assaulted by a brutal dictator, plead for weapons to unseat Bashar al-Assad. Clinging to power appears to be Assad’s main goal in life, even if he must slaughter civilians to do it. The poorly-armed opposition asks for weapons to equalize the conflict.

The war in Syria is a conundrum, a problem that appears to have no favorable resolution. The opposition, assaulted by a brutal dictator, plead for weapons to unseat Bashar al-Assad. Clinging to power appears to be Assad’s main goal in life, even if he must slaughter civilians to do it. The poorly-armed opposition asks for weapons to equalize the conflict. The use of chemical weapons is “a red line,” so we are told. What then is our response? What are our plans? We are weary of war. Chemical weapons apparently is the one step Assad could take which would bring retribution on him. But will we be able to act effectively?

The use of chemical weapons is “a red line,” so we are told. What then is our response? What are our plans? We are weary of war. Chemical weapons apparently is the one step Assad could take which would bring retribution on him. But will we be able to act effectively?