Uncomfortable Sunday best clothes. Curtailment of sports and recreational pastimes. Long, boring sermons.

These are pictures we retain of puritanical Sabbath laws. Trish Harrison Warren suggests a different purpose for a Sabbath rest. (“How to Fight Back Against Inhumanity at Modern Work,” The New York Times, October 16, 2022.)

Today, Warren suggests, we need to revisit the Sabbath again: “When a careerist culture meets a digital revolution that allows unlimited access to work, something’s got to give.”

For workers in the beginning of the industrial revolution, who often toiled from sunup to sundown six days a week, a day off was a much needed day of rest, a day to connect with family, and perhaps to think of a deeper meaning for life. After all, in many ancient cultures, slaves and menial workers had no days off. One day was very much like any other. Surely, the beginning of a Christian Sabbath would have been welcome.

For several years of my life, I worked as a computer programmer. Most of what I did was, to me, boring and without meaning. I commuted to the city, swiped my badge before entering the work place, and settled in to staring at a computer, making minute changes for hours to computer programs.

I can understand why workers, working more and more on remote computer stations, would prefer at least the benefit of doing their jobs in a comfortable home setting. They at least can wear comfortable clothes, eat their own meals, and forgo a time-consuming commute. But, of course, if work can be done at home, one is indeed not limited by commutes or a set number of hours.

Computer monitoring also may mean that those who work selling to the public can be tasked minutely even to the bathroom breaks they take. Forget stopping to chat with a fellow worker and fostering a human connection.

Writes Warren, “The labor movement fought to change both culture and policy to limit our work weeks, and the 40-hour work week eventually became a norm.”

Today, we’re again overdue for a humanizing of work practices in keeping with our latest machine revolution.

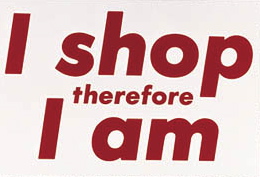

Or Americans could continue to work as they had and buy more and more things. Once “things” became the goal of work, however, the desire for more and more material goods required greater commitment to job and career.

Or Americans could continue to work as they had and buy more and more things. Once “things” became the goal of work, however, the desire for more and more material goods required greater commitment to job and career.