Few Americans under forty remember the seizure of the American embassy in Iran in 1979 by Iranian radicals, followed by the imprisonment of fifty-two American diplomats for 444 days. Many hostages, after their release, went on to productive lives. Others suffered severe emotional damage that they and their families carry to this day because of torture and inhumane conditions.

The Cuban revolution happened in the late fifties, many years before the Iranian crisis. It affected more people, however, and Cuban-Americans live among us who fled Castro’s dictatorship since then and who can tell us of wrongs committed by that government.

Both Iran and Cuba practice human rights violations. But some of our allies do also. Saudi Arabia and Egypt come to mind. That does not excuse their human rights abuses. It means that we find it in our interests to have diplomatic ties. Choosing not to have relations appears to do nothing to stop human rights violations.

We broke ties with Cuba half a century ago because it was a nation on our doorstep allied with the Soviet Union. The Cuban missile crisis was real, but the Soviet Union no longer exists. Neither Russia nor Venezuela (a supporter of Cuba) are able to offer the aid they once did.

Iran is more difficult. Iran wants to become a major power in the Middle East. If Iranians are not subject to nuclear inspections, they will most likely develop a nuclear weapon. If they are subject to inspections, they have less chance of doing so.

We tried military intervention in Iraq. It cost us dearly and multiplied our problems in the Middle East. Why do we suppose any military “solution” we might inflict on Iran would end differently? Get real.

While accepting that we have serious concerns with both countries, can we not forge a more intelligent relationship with Cuba and Iran? One that has more chance of success than failed policies of the past?

The Russian currency has tumbled in the world money markets. A combination of circumstances contributed. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s actions in the Ukraine led to sanctions by Europe and the U.S. In addition, it’s not a happy time for oil producers like Russia, as oil prices have reached historic lows.

The Russian currency has tumbled in the world money markets. A combination of circumstances contributed. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s actions in the Ukraine led to sanctions by Europe and the U.S. In addition, it’s not a happy time for oil producers like Russia, as oil prices have reached historic lows. December 7, my calendar notes, is Pearl Harbor Day. The day commemorates lives lost in the attack on the U.S. naval base in Hawaii by Japanese forces in 1941. It led immediately to our entry into World II.

December 7, my calendar notes, is Pearl Harbor Day. The day commemorates lives lost in the attack on the U.S. naval base in Hawaii by Japanese forces in 1941. It led immediately to our entry into World II. In an article in the Foreign Service Journal (January, 2012), Margaret Sullivan recounted her early years in China as the daughter of an American missionary teacher when Japanese forces took over China. Ms. Sullivan remembers a Japanese soldier smiling at her family as they went through a checkpoint.

In an article in the Foreign Service Journal (January, 2012), Margaret Sullivan recounted her early years in China as the daughter of an American missionary teacher when Japanese forces took over China. Ms. Sullivan remembers a Japanese soldier smiling at her family as they went through a checkpoint. Jubilant crowds from East and West Germany began crossing it and hammering off pieces in 1989, as the Communist East collapsed. From the beginning, the Wall symbolized failure. What successful nation must build a wall to force its citizens to remain?

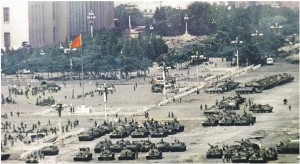

Jubilant crowds from East and West Germany began crossing it and hammering off pieces in 1989, as the Communist East collapsed. From the beginning, the Wall symbolized failure. What successful nation must build a wall to force its citizens to remain? You may see the term “Tiananmen Square” frequently in the news this next week. A quarter century ago, a movement in that square in Beijing, China, for more democracy, was crushed by authorities in June, 1989. Hundreds of students are estimated to have been killed, perhaps more.

You may see the term “Tiananmen Square” frequently in the news this next week. A quarter century ago, a movement in that square in Beijing, China, for more democracy, was crushed by authorities in June, 1989. Hundreds of students are estimated to have been killed, perhaps more. Spring, 1989, had seen the movement in China smothered by the military. However, in November of that same year, the barrier between East and West Germany in Berlin—”the Wall”—fell.

Spring, 1989, had seen the movement in China smothered by the military. However, in November of that same year, the barrier between East and West Germany in Berlin—”the Wall”—fell. This period was a beginning, not of leaving my faith, but of finding a more mature faith. Before in my world, Christians were Christians, and the rest was everybody else. Now I began to see graduations within the Christian community as well as in the community of “others.” I found that I could disagree but respect those who differed with me. I am, as the apostle Paul said, still working out my own salvation with fear and trembling.

This period was a beginning, not of leaving my faith, but of finding a more mature faith. Before in my world, Christians were Christians, and the rest was everybody else. Now I began to see graduations within the Christian community as well as in the community of “others.” I found that I could disagree but respect those who differed with me. I am, as the apostle Paul said, still working out my own salvation with fear and trembling. I also came to understand that some people who called themselves Christians have committed grievous sins against others. We worship Jesus who, though equal with God, humbled himself to become like us. Yet, in our arrogance, we scream at the different others as though we are God and know perfection. Now I am more aware of my own potential for error and am more willing to listen to other viewpoints.

I also came to understand that some people who called themselves Christians have committed grievous sins against others. We worship Jesus who, though equal with God, humbled himself to become like us. Yet, in our arrogance, we scream at the different others as though we are God and know perfection. Now I am more aware of my own potential for error and am more willing to listen to other viewpoints. I find no fault in Jesus, but I fear that we have clung, not to Jesus and his radical love, but to something less, Christianity as a mere civil religion. Perhaps that is why Christianity is no longer the default religion in the Western world.

I find no fault in Jesus, but I fear that we have clung, not to Jesus and his radical love, but to something less, Christianity as a mere civil religion. Perhaps that is why Christianity is no longer the default religion in the Western world.