Youcef Nadarkhani, a Christian pastor in Iran, has been jailed since October, 2009, for issues related to his faith. Recently a letter, reportedly from him and written in prison, was released by Present Truth Ministries. I don’t know if the pastor wrote it in English or it was translated, but I quote the entire letter as I found it. It is longer than my usual blog. I justify the length because I am touched by echos in the letter reminiscent of New Testament letters written by the apostle Paul while in prison,. The letter follows:

Greetings from your servant and younger brother in Christ, Youcef Nadarkhani.

Greetings from your servant and younger brother in Christ, Youcef Nadarkhani.

To: All those who are concerned and worried about my current situation.

First, I would like to inform all of my beloved brothers and sisters that I am in perfect health in the flesh and spirit. And I try to have a little different approach from others to these days, and consider it as the day of exam and trial of my faith. And during these days which are hard in order to prove your loyalty and sincerity to God, I am trying to do the best in my power to stay right with what I have learned from God’s commandments.

I need to remind my beloveds, though my trial due has been so long, and as in the flesh I wish these days to end, yet I have surrendered myself to God’s will.

I am neither a political person nor do I know about political complicity, but I know that while there are many things in common between different cultures, there are also differences between these cultures around the world which can result in criticism, which most of the times response to this criticisms will be harsh and as a result will lengthen our problems.

From time to time I am informed about the news which is spreading in the media about my current situation, for instance being supported by various churches and famous politicians who have asked for my release, or campaigns and human rights activities which are going on against the charges which are applied to me. I do believe that these kind of activities can be very helpful in order to reach freedom, and respecting human rights in a right way can bring forth positive results.

I want to appreciate all those are trying to reach this goal. But at the other hand, I’d like to announce my disagreement with the insulting activities which cause stress and trouble, which unfortunately are done with the justification (excuse) of defending human rights and freedom, for the results are so clear and obvious for me.

I try to be humble and obedient to those who are in power, obedience to those in authority which God has granted to the officials of my country, and pray for them to rule the country according to the will of God and be successful in doing this. For I know in this way I have obeyed God’s word. I try to obey along with those whom I see in a common situation with me. They never had any complaint, but just let the power of God be manifested in their lives, and though sometimes we read that they have used this right to defend themselves, for they had this right, I am not an exception as well and have used all possibilities and so forth and am waiting for the final result.

So I ask all the beloved ones to pray for me as the holy word has said. At the end I hope my freedom will be prepared as soon as possible, as the authorities of my country will do with free will according to their law and commandments which are answerable to.

May God’s Grace and Mercy be upon you now and forever. Amen.

Youcef Nadarkhani

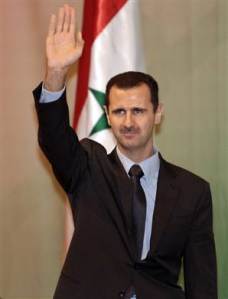

The situation has improved for Christians of the Orthodox persuasion. In fact, Russian President Vladimir Putin stands accused of using the Russian Orthodox church as a means of bolstering his less than democratic regime. Some Russians are concerned by the power the church appears to be gaining in Putin’s government. Reports suggest that the church’s influence may be one reason for Russia’s support of the bloody Assad regime in Syria.

The situation has improved for Christians of the Orthodox persuasion. In fact, Russian President Vladimir Putin stands accused of using the Russian Orthodox church as a means of bolstering his less than democratic regime. Some Russians are concerned by the power the church appears to be gaining in Putin’s government. Reports suggest that the church’s influence may be one reason for Russia’s support of the bloody Assad regime in Syria. Syria is Russia’s remaining ally in the Middle East and hosts a Russian naval base. The church, rightly, is concerned about the fate of their fellow Orthodox believers in Syria should the Assad regime fall and be replaced by a possibly Islamist government. However, to suggest that Assad should be allowed to slaughter innocent civilians so that Christians might—possibly—be better protected, seems contrary to Jesus’ teachings, to say the least.

Syria is Russia’s remaining ally in the Middle East and hosts a Russian naval base. The church, rightly, is concerned about the fate of their fellow Orthodox believers in Syria should the Assad regime fall and be replaced by a possibly Islamist government. However, to suggest that Assad should be allowed to slaughter innocent civilians so that Christians might—possibly—be better protected, seems contrary to Jesus’ teachings, to say the least. Greetings from your servant and younger brother in Christ, Youcef Nadarkhani.

Greetings from your servant and younger brother in Christ, Youcef Nadarkhani.