Eric X. Li, writing in Foreign Affairs (“The Life of the Party; The Post-Democratic Future Begins in China,” Foreign Affairs, January/February, 2013) states:

“While China’s might grows, the West’s ills multiply: since winning the Cold War, the United States has, in one generation, allowed its middle class to disintegrate. Its infrastructure languishes in disrepair, and its politics, both electoral and legislative, have fallen captive to money and special interests.”

We may question Eric X. Li’s belief that China’s example of governance is ultimately good for humankind, but we surely understand that events in the United States in recent years have demonstrated a less than sterling example of democracy for the rest of the world.

For several decades, American soldiers and diplomats have risked lives to bring democracy to countries that seem not to know what to do with it. We berate them for disintegrating into warring tribes.

Perhaps we should examine our own warring tribes. Democracy works only when a people evidence humility as regards their own opinions and show respect for those with whom they disagree. Hatred poisons democracy. We may be deeply saddened at certain trends, but we self-destruct if our response is to allow this poison to infect us.

None of us will obtain all we wish. We live in an imperfect world. Respect and compromise grease the wheels of democracy so that it works.

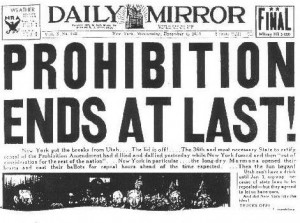

Such was the case with the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Ratified in 1919, it prohibited intoxicating beverages. A backlash against it, however, led to its repeal in 1933. Too many people made “bathtub” gin or bought bootleg liquor (leading to an increase in organized crime) for the amendment to work.

Such was the case with the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Ratified in 1919, it prohibited intoxicating beverages. A backlash against it, however, led to its repeal in 1933. Too many people made “bathtub” gin or bought bootleg liquor (leading to an increase in organized crime) for the amendment to work. The literature wasn’t an intelligent discussion of a point of view, but epithet hurling diatribes.

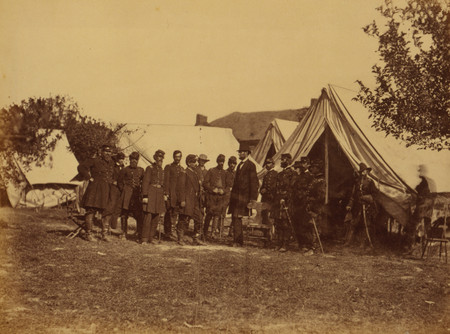

The literature wasn’t an intelligent discussion of a point of view, but epithet hurling diatribes. Otherwise reasonable people became too angry to discuss differences. Southerners cared more for their cotton economy and its slave labor than in justice. The North knew its own exploitation of immigrant labor, yet often saw itself as superior and worked from a position of self-righteousness in dealing with the slavery issue.

Otherwise reasonable people became too angry to discuss differences. Southerners cared more for their cotton economy and its slave labor than in justice. The North knew its own exploitation of immigrant labor, yet often saw itself as superior and worked from a position of self-righteousness in dealing with the slavery issue. The United States is one of the world’s oldest democratic republics, but democracy as practiced here is very much a work in progress. Its continuance is not guaranteed. Politics and power weave uneasily through our relatively new experiment in democracy.

The United States is one of the world’s oldest democratic republics, but democracy as practiced here is very much a work in progress. Its continuance is not guaranteed. Politics and power weave uneasily through our relatively new experiment in democracy. Benjamin Franklin is said to have remarked at the signing of the Declaration of Independence: “Gentleman, we must all hang together or, assuredly, we shall hang separately.”

Benjamin Franklin is said to have remarked at the signing of the Declaration of Independence: “Gentleman, we must all hang together or, assuredly, we shall hang separately.”