The African country of Rwanda was devastated by horrible massacres of one ethnic group by another in 1994. An estimated 500,000 to 800,000 were murdered in genocidal attacks merely for being born into a particular ethnic group.

The Nazi genocide of European Jews remains the best known example of this kind of atrocity—the attempted extermination of one group of people by another. People are hunted and murdered merely because they are born into that group.

David Rawson, the U.S. ambassador to Rwanda when the massacre occurred, discussed the need to better understand and prevent such atrocities.(“Predicting and Preventing Intrastate Violence; Lessons from Rwanda,” The Foreign Service Journal, September 2019)

He states: “Great powers are reluctant to intervene, especially in little countries off the radar scope of their national interests.”

After all, with the results of our now-regrettable intervention in countries like Iraq, who wants to send our troops to yet another trouble spot?

Writing in the same issue of The Foreign Service Journal (“Getting Preventive Stabilization on the Map”) , David C. Becker and Steve Lewis suggest a cheaper way: going after movements before they become conflicts.

Neither article is especially optimistic, but the idea of prevention suggests a glimmer of hope. Prevention includes the requirement to work with local partners “and a willingness to take modest risks with meager resources.”

An example was cited of a few aid agency groups in Indonesia who encouraged talks between Christian and Muslim community leaders. The talks led to the realization that outside groups were trying to encourage violence, leading the locals to repudiate such violence.

A quote based on conversation attributed to Winston Churchill says: ““Jaw-jaw is always better than war-war.”

Talking is certainly less expensive in lives and resources. And who knows? It may work.

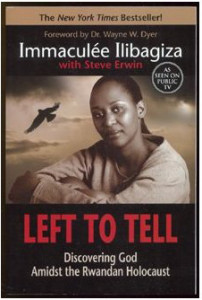

Immaculée Ilibagiza, a young woman born in Rwanda, tells of her horrifying time during the Rwandan massacres that began in April, 1994, twenty years ago this month. Most of her family were slaughtered. Hidden in a bathroom with seven other women, she endured ninety-one days of cramped hiding. She tells her story in Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust.

Immaculée Ilibagiza, a young woman born in Rwanda, tells of her horrifying time during the Rwandan massacres that began in April, 1994, twenty years ago this month. Most of her family were slaughtered. Hidden in a bathroom with seven other women, she endured ninety-one days of cramped hiding. She tells her story in Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust.