Culture Shock

Kate, the female protagonist in Singing in Bab ylon, is overwhelmed after she lands at the Abdul Aziz International Airport in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. She’s never been out of the United States before.

ylon, is overwhelmed after she lands at the Abdul Aziz International Airport in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. She’s never been out of the United States before.

The airport resembles most modern airports, but the people don’t, because of their clothing. Most of the women are in black robes, called abiyahs. Many wear black scarves on their heads as well, and a few wear veils and gloves. Many of the men wear white robes called thobes and cover their heads with a white or checkered cloth held by an elastic-looking band. I was told that the band was traditionally a hobble for camels.

Though she may have heard Spanish, this is the first time for Kate in a place where so few people are speaking English. She blinks at the guttural language she knows must be Arabic.

A Life Apart

When I stepped off the plane in Jeddah in December, 1990, I had the advantage over Kate of having my American sponsors meet me and take me where I would live. My home over the next two years was a bungalow on the U.S. consulate compound. Most Westerners live within walled compounds, where they can dress and live as they please. (Also, in the age of terrorist attacks, the compounds are more easily protected.) The compounds often have a pool, and the larger ones may have other amenities like tennis courts, and perhaps a grocery store and a restaurant. Extremely large ones may operate as small cities.

Rules for Women

Rules for Women

Like Kate, I couldn’t drive a car. Women are forbidden to do so in Saudi Arabia except on some of the compounds. That may eventually change as more women defy the law. When I was there, however, it was strictly enforced.

More than driving, I missed strolling around by myself outside the compound. Women simply did not walk alone, except in malls, of which Jeddah boasted several modern ones. Most women wore abiyahs there, too, and were waited on by men. No female salesclerks.

Cultural Consequences

If you broke any of the rules, like not wearing an abiyah, you risked being stopped by a Mutawwa. He was the representative of an official group loosely translated as the society for the preservation of virtue and the elimination of vice. Sometimes the Mutawwa carried a stick with which to whack the ankles of errant shoppers.

Nevertheless, it’s too easy to poke fun at some of the customs. Best to remember that the customs were more strictly enforced after Westerners introduced threatening lifestyles, including excessive drinking, pornographic material, and drugs. Yes, some of the reactions are absurd by our standards, but they should be understood as an ancient society’s way of coping with outside practices that most of its members don’t want for their children.

Recently, Twitter has found its way into Saudi society, as this article explains.

Whimsy and Hospitality

One of my favorite places to go in Jeddah was the Corniche, a boulevard on the shores of the Red Sea beside Jeddah. Giant and sometimes whimsical sculptures graced the drive: a teapot, a seagull, a bicycle. Restaurants and parks lined it. On weekends, families enjoyed meals and tea and strolls. Sometimes in the cool of an evening, my friends and I stopped in one of the restaurants for a local dessert called Umm Ali (Mother of Ali). I remember it as a deliciously sweet bread pudding with nuts and raisins.

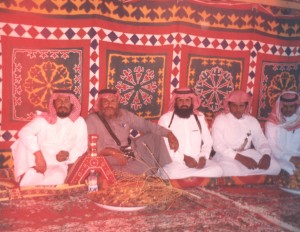

The hospitality of Arabs is legendary and deservedly so. “Eat as much as you love us,” one Saudi said, as he heaped my plate with more food than I could possibly eat. I will always remember an old Saudi gentleman helping me to choice bits of meat at a desert goat grab. That’s my favorite image of Saudi Arabia.

Photo Album

|

|

|

|