Attack ads, slogans, and sound bytes harm because they obscure. Climate change, cyber warfare, and economic recessions cannot be explained in a few words. Conflicts in Syria and Ukraine pit al-Qaeda and different ethnic groups into an alphabet of amorphous foes. They require a more intelligent probing than is found in a few celebrity-studded newscasts.

The new world order requires a citizenry that thinks.

The Nazis came to power in Germany in a society of educated, middle class citizens. An unsuccessful war and economic problems led a significant proportion of the population to look for simple solutions like blaming Jews. Instead they might have examined issues like the world wide recession and its effects on Germany. They might have found a way to deal with the heavy debt placed on the country by the treaty that ended World War I. Instead, they allowed themselves to be caught in the hyper nationalism championed by the Nazis.

The Nazis came to power in Germany in a society of educated, middle class citizens. An unsuccessful war and economic problems led a significant proportion of the population to look for simple solutions like blaming Jews. Instead they might have examined issues like the world wide recession and its effects on Germany. They might have found a way to deal with the heavy debt placed on the country by the treaty that ended World War I. Instead, they allowed themselves to be caught in the hyper nationalism championed by the Nazis.

Start thinking with this article. Based on a study, it asks if the United States can still claim to be a democracy.

For the next episode, I was privileged to work closer to the front lines. I was in Saudi Arabia working for the State Department when the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was defeated by the first alliance since World War II that included Russia.

For the next episode, I was privileged to work closer to the front lines. I was in Saudi Arabia working for the State Department when the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was defeated by the first alliance since World War II that included Russia. Vladimir Putin in Russia, Bashar al-Assad in Syria, and the generals in Egypt, among others, push against what a short time ago seemed an unstoppable march to self-government.

Vladimir Putin in Russia, Bashar al-Assad in Syria, and the generals in Egypt, among others, push against what a short time ago seemed an unstoppable march to self-government. Ukraine has recently struggled to return to democracy but it is hampered by the leftovers of a corrupt regime. Russia’s Putin took advantage of the country’s weakness. That is often the way dictators amass power.

Ukraine has recently struggled to return to democracy but it is hampered by the leftovers of a corrupt regime. Russia’s Putin took advantage of the country’s weakness. That is often the way dictators amass power. We live less than a hundred miles from the huge landslide in Oso, Washington, the tragedy that killed over twenty people. Several are still missing.

We live less than a hundred miles from the huge landslide in Oso, Washington, the tragedy that killed over twenty people. Several are still missing. Yet the blood marked face of the little girl in Aleppo, Syria, stares out of the picture, uncomprehending as to why one would want to hurt her. She is dressed attractively. Her family must love her very much, and perhaps she will survive. Others, surely, are more damaged by the barrel bombs, full of shrapnel and nails. The bombs do not differentiate between military and civilian. Those who employ them do not intend that they should.

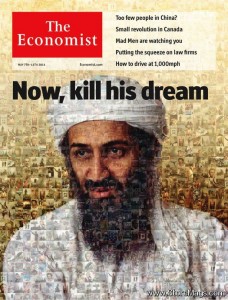

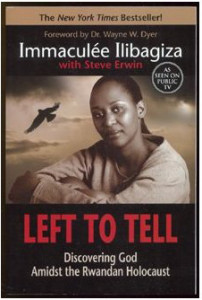

Yet the blood marked face of the little girl in Aleppo, Syria, stares out of the picture, uncomprehending as to why one would want to hurt her. She is dressed attractively. Her family must love her very much, and perhaps she will survive. Others, surely, are more damaged by the barrel bombs, full of shrapnel and nails. The bombs do not differentiate between military and civilian. Those who employ them do not intend that they should. Immaculée Ilibagiza, a young woman born in Rwanda, tells of her horrifying time during the Rwandan massacres that began in April, 1994, twenty years ago this month. Most of her family were slaughtered. Hidden in a bathroom with seven other women, she endured ninety-one days of cramped hiding. She tells her story in Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust.

Immaculée Ilibagiza, a young woman born in Rwanda, tells of her horrifying time during the Rwandan massacres that began in April, 1994, twenty years ago this month. Most of her family were slaughtered. Hidden in a bathroom with seven other women, she endured ninety-one days of cramped hiding. She tells her story in Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust. 2. Rural Muslims tend to become more conservative when they move to the city. Nomadic Arabs that we met while in the desert appeared less strict in matters of dress and other habits than their urban cousins. This reminded me of the denomination I know best, Southern Baptists. Southern Baptists became more conservative when they left their rural roots. In 1990, Nancy Ammerman, then a professor at Emory University, wrote Baptist Battles: Social Change and Religious Conflict in the Southern Baptist Convention, which portrays this shift.

2. Rural Muslims tend to become more conservative when they move to the city. Nomadic Arabs that we met while in the desert appeared less strict in matters of dress and other habits than their urban cousins. This reminded me of the denomination I know best, Southern Baptists. Southern Baptists became more conservative when they left their rural roots. In 1990, Nancy Ammerman, then a professor at Emory University, wrote Baptist Battles: Social Change and Religious Conflict in the Southern Baptist Convention, which portrays this shift. 5. Some Muslims are dismayed at the infiltration of Western culture into their own. One of their writers called it “westoxification.”

5. Some Muslims are dismayed at the infiltration of Western culture into their own. One of their writers called it “westoxification.” I have a cartoon in my files from 2008 when Russia invaded the country of Georgia. David Horsey drew the political cartoon for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Georgia, located between Europe and Asia, choose to leave the Soviet sphere after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. In 2008, the Soviet Union invaded and annexed portions of their former satellite. The reactions were similar to our reactions today to Russia’s designs on the Ukraine.

I have a cartoon in my files from 2008 when Russia invaded the country of Georgia. David Horsey drew the political cartoon for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Georgia, located between Europe and Asia, choose to leave the Soviet sphere after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. In 2008, the Soviet Union invaded and annexed portions of their former satellite. The reactions were similar to our reactions today to Russia’s designs on the Ukraine. The U.S. has issued visa sanctions against several Russian tycoons in protest of the Russian takeover in Crimea, meaning the tycoons will be prohibited from visits to the U.S.

The U.S. has issued visa sanctions against several Russian tycoons in protest of the Russian takeover in Crimea, meaning the tycoons will be prohibited from visits to the U.S. Russia’s Putin appears only one of many neo dictators, snatching a country back into the age of baronial privilege, in which favored elites rob the country of its wealth and ignore wishes of the majority. Ancient tribal hatreds threaten Libya. Egypt seems turned back toward another military government. South Sudan is again wracked by mayhem. Atrocities by a ruling minority group in Syria rival those of the Holocaust.

Russia’s Putin appears only one of many neo dictators, snatching a country back into the age of baronial privilege, in which favored elites rob the country of its wealth and ignore wishes of the majority. Ancient tribal hatreds threaten Libya. Egypt seems turned back toward another military government. South Sudan is again wracked by mayhem. Atrocities by a ruling minority group in Syria rival those of the Holocaust.