On Good Friday, in preparation for Easter, a few Christians in the Middle Eastern country of Syria meditated and prayed. They gathered within the walls of an ancient monastery, Deir Mar Musa. During years of conflict and suffering, this monastery has endured, a witness for peace in a war ravaged country.

Suddenly a Muslim young man entered into a quiet corner of the monastery. He also was a searcher for a place to pray. He spread his prayer rug, then began his prayers. A photographer, Cécile Massie, there to observe the monastic community in Good Friday meditations, snapped the picture of the Christians and the young man in their prayers (Stephanie Saldaña, “All Sorts of Little Things: On Compassion in a Time of War,” Plough Quarterly, Summer, 2018).

Writes Saldaña: “Together and separately the Muslim and Christian faithful turn toward God. This shared prayer—and with it a hope—enters into our suffering and becomes known.”

In the midst of unprecedented numbers of refugees and victims of hatred and war, she identifies the meaning of compassion as “to suffer with.” She means to suffer with all, not just those of our religious persuasion.

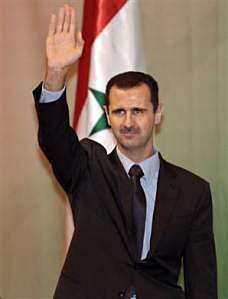

The war in Syria is a conundrum, a problem that appears to have no favorable resolution. The opposition, assaulted by a brutal dictator, plead for weapons to unseat Bashar al-Assad. Clinging to power appears to be Assad’s main goal in life, even if he must slaughter civilians to do it. The poorly-armed opposition asks for weapons to equalize the conflict.

The war in Syria is a conundrum, a problem that appears to have no favorable resolution. The opposition, assaulted by a brutal dictator, plead for weapons to unseat Bashar al-Assad. Clinging to power appears to be Assad’s main goal in life, even if he must slaughter civilians to do it. The poorly-armed opposition asks for weapons to equalize the conflict. The use of chemical weapons is “a red line,” so we are told. What then is our response? What are our plans? We are weary of war. Chemical weapons apparently is the one step Assad could take which would bring retribution on him. But will we be able to act effectively?

The use of chemical weapons is “a red line,” so we are told. What then is our response? What are our plans? We are weary of war. Chemical weapons apparently is the one step Assad could take which would bring retribution on him. But will we be able to act effectively? The issue of chemical weapons hovers over the conflict. Bashar al-Assad has chemical weapons and has threatened to use them. No one doubts the brutality of the al-Assad famly. The father of Bashar massacred and obliterated the village of Hama in 1982 because of its opposition to his rule.

The issue of chemical weapons hovers over the conflict. Bashar al-Assad has chemical weapons and has threatened to use them. No one doubts the brutality of the al-Assad famly. The father of Bashar massacred and obliterated the village of Hama in 1982 because of its opposition to his rule.

The situation has improved for Christians of the Orthodox persuasion. In fact, Russian President Vladimir Putin stands accused of using the Russian Orthodox church as a means of bolstering his less than democratic regime. Some Russians are concerned by the power the church appears to be gaining in Putin’s government. Reports suggest that the church’s influence may be one reason for Russia’s support of the bloody Assad regime in Syria.

The situation has improved for Christians of the Orthodox persuasion. In fact, Russian President Vladimir Putin stands accused of using the Russian Orthodox church as a means of bolstering his less than democratic regime. Some Russians are concerned by the power the church appears to be gaining in Putin’s government. Reports suggest that the church’s influence may be one reason for Russia’s support of the bloody Assad regime in Syria. Syria is Russia’s remaining ally in the Middle East and hosts a Russian naval base. The church, rightly, is concerned about the fate of their fellow Orthodox believers in Syria should the Assad regime fall and be replaced by a possibly Islamist government. However, to suggest that Assad should be allowed to slaughter innocent civilians so that Christians might—possibly—be better protected, seems contrary to Jesus’ teachings, to say the least.

Syria is Russia’s remaining ally in the Middle East and hosts a Russian naval base. The church, rightly, is concerned about the fate of their fellow Orthodox believers in Syria should the Assad regime fall and be replaced by a possibly Islamist government. However, to suggest that Assad should be allowed to slaughter innocent civilians so that Christians might—possibly—be better protected, seems contrary to Jesus’ teachings, to say the least. In those earlier times, the U.S. was accused of supporting dictatorial regimes in certain African and South American countries because the regimes touted themselves as anti-communist. Now the U.S. is accused of propping up former dictators like Ben Ali in Tunisia and Mubarak in Egypt. These men clamped down on the growth of Islamists in their countries, so we supported them even if they employed brutal methods. Egypt, especially, became a huge recipient of U.S. aid.

In those earlier times, the U.S. was accused of supporting dictatorial regimes in certain African and South American countries because the regimes touted themselves as anti-communist. Now the U.S. is accused of propping up former dictators like Ben Ali in Tunisia and Mubarak in Egypt. These men clamped down on the growth of Islamists in their countries, so we supported them even if they employed brutal methods. Egypt, especially, became a huge recipient of U.S. aid. In my novel Singing in Babylon, the female protagonist, Kate, moves to Saudi Arabia from her native Tennessee to teach. She travels for her first time outside the United States. On a drive with her friend, Philip, an American journalist on assignment to the Middle East, she notices a veiled and gloved woman pushing a child on a swing in a public park. The woman glances at the unveiled Kate, and Kate wonders how the woman feels about this Western female’s intrusion into her world.

In my novel Singing in Babylon, the female protagonist, Kate, moves to Saudi Arabia from her native Tennessee to teach. She travels for her first time outside the United States. On a drive with her friend, Philip, an American journalist on assignment to the Middle East, she notices a veiled and gloved woman pushing a child on a swing in a public park. The woman glances at the unveiled Kate, and Kate wonders how the woman feels about this Western female’s intrusion into her world. Fast food restaurants, unveiled women, and automobiles bring unprecedented freedom and rapid change to a nation in one or two generations. These changes arrived in a country accustomed to centuries-old merchant towns, Bedouins herding camels and goats, and ancient tribes familiar with the customs of generations.

Fast food restaurants, unveiled women, and automobiles bring unprecedented freedom and rapid change to a nation in one or two generations. These changes arrived in a country accustomed to centuries-old merchant towns, Bedouins herding camels and goats, and ancient tribes familiar with the customs of generations.