Sometimes when things I’ve prayed for actually happen, I’ve found joy, of course, but I’m also surprised by the fear that lurks as well. This was the case when I finally realized my dream of starting a journey to a new job allowing me to work and live in a foreign country, something I’d wanted to do since I had read books in my childhood about other countries.

A diary I kept of my first overseas travel shows my ambivalence:

“Picture, if you will: I’m checking in at JFK Airport for the first international flight of my life. They are asking me things like:

‘Who packed your luggage?’ ‘Who does your luggage belong to?’ ‘Has your luggage ever been out of your sight?’ ‘Has anyone given you anything to take with you?’ I decide the encouraging letter my Christian friends gave me before the journey is not the sort of thing they are talking about and refrain from mentioning it.

“The questions do not allay the nervousness I’m beginning to experience—my stomach feels funny . . .We board the plane. The pilot announces that we are going to be delayed by ‘slight’ maintenance problems. I wish he would be more specific. Then again, maybe I don’t.

“Finally, we take off. . .. I cannot see anything except a tiny bit of the wing . . .I remember being told that the tail section is the safest place to be.

“When we are safely airborne, the pilot comes on to announce that we are going to be in Frankfort one-half hour sooner than planned because of a hyperactive jet stream. That, he says, is the good news. The bad news is that we will experience some turbulence.” Both predictions prove true.

Looking back over my diary now, I think about what lay ahead. Fortunately, it included a safe trip all the way to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, my first Foreign Service post. I did manage to pick up the wrong luggage at one of the stops on the way. We corrected this, not only to my relief, but no doubt to the relief of the woman whose luggage I had mistakenly grabbed (it was the same color as mine.) She was coming to visit her husband in the military, preparing for the Desert Storm invasion of Iraq.

This happened to be right before the beginning of that first war with Iraq in 1990. Needless to say, it proved to be an interesting time to be in Saudi Arabia. Thankfully, I made close friends and grew in my Christian faith during this time. Believe me, I did grow.

Looking over that time now, I think about the saying attributed to Otto von Bismark: “There is a Providence that protects idiots, drunkards, children and the United States of America.” Providence certainly protected the child that was me and my need to learn and grow, despite my childish ignorance.

I think I can say that for me following what I believed to be God’s will has ranged from enabling to terrifying to, ultimately, a newer understanding of grace and care.

Because I really needed that grace and care.

Tag Archives: Saudi Arabia

Stepping Out

The Pan American Boeing 747 taxied down a runway of the JFK airport around 9 p.m. on December 4, 1990, and lifted off. I watched the New York City metropolitan area spreading out in a vast sea of lights. It was the first international plane trip of my life. I was beginning my first assignment as a U.S. Foreign Service officer.

The takeoff began my trip to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, with a change of planes in Frankfurt, Germany, then to Riyadh. In Riyadh, I was to change planes again for a final short flight to Saudi Arabia’s port city of Jeddah.

Looking back, I have to laugh at all the mistakes a hyped up newbie Foreign Service officer could make. I had packed my suitcase too full, and it was obvious, once I landed in New York City for consultations, that it wasn’t going to last out the trip.

Fortunately, a kind officer in the New York office of the Immigration and Naturalization Service took me to a luggage store for a better suitcase.

Of course, the new suitcase was possibly the reason I identified the wrong one when I, seriously jet lagged, changed planes in Riyadh. Eventually, the luggage was sent back to the right person in Riyadh, and mine returned to me in a day or so.

However, due to the fact that I had no luggage for my first evening in Jeddah, I had to attend a welcoming reception wearing the travel-stained outfit I’d worn for several days. I also developed a blister on my foot from walking around in my travel shoes.

My first assignment began a few weeks before the the start of the First Gulf War. It pitted Iraq against Saudi Arabia, with the United States and other allies supporting Saudi Arabia.

Due to new assignments and training, the former officer had been transferred to another job before I arrived, so I missed training with the one I was replacing. I fell into my visa services job with no overlap as the war began.

After daytime duties in the visa section (overflowing with foreign nationals seeking visas to leave the country now coveted by Saddam Hussein), I worked in the control room in the evenings. This operation was a command center overseeing American wartime activities, including supervising high level U.S. officials coming to confer with Saudi Arabian officials on the war efforts.

I not only survived but treasured that first foreign assignment as a time of comradery with fellow Americans seeking to serve our country in a time of crisis.

I had joined the Foreign Service with the hope of living in other countries and enjoying an exciting and meaningful vocation. I was not disappointed.

Power Off Here; Children Dying There

A windstorm blew through our island community this week. The power flickered off about ten in the evening. We went to bed under our quilts. By next morning, power was restored, as we expected. Safe in a peaceful community, we had never doubted we would again have heat and food and hot water.

But even as we waited, securely, for normality, recent scenes haunted me from Yemen, in the Middle East, where nothing is ever normal and children die a slow death from starvation.

We have taken the side of Saudi Arabia against Yemen, war ravaged for years, though few Americans have any idea about what is going on there.

The bloodletting is part of an ancient struggle, begun in the seventh century, between different branches of Islam—Sunni and Shia. Saudi Arabia is the Sunni leader. Iran, descendant of ancient Persia, is the Shia leader.

We’re mainly interested in the oil pumped from Saudi Arabia. That and the money we make from selling arms to them. Oh, yes, also, Iran has become public enemy number one, and we want Saudi Arabia’s backing against them.

Neither side is pure, of course.

Iranians stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran in 1979 and imprisoned our diplomats for 444 days. They also sponsor Hezbollah, a political and militant group in Lebanon.

On the other hand, fifteen of the nineteen terrorists who attacked our country on September 11, 2001,were from Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia sponsors that war against Yemen.

You can blame either side, if you like.

For me, though, taking sides becomes irrelevant next to children slowly dying from starvation as helpless parents watch. Others have been bombed by weapons we sold to the Saudis.

I don’t care who you choose as your enemy, but what we have abetted and allowed is a sin against God.

You Can’t Return to the Past, Except Maybe in a Book

As a newbie U.S. Foreign Service officer in the early 1990’s, I remember my first assignment in Saudi Arabia as a marvelous adventure. It was as exciting as the stories I used to read in my childhood.

I visited exotic market places with new friends, walked through ancient ruins, and fell in love with Middle Eastern food. Once in a while I took leave to visit Europe, exploring countries I had only read about.

My career began before terrorism led to intrusive pre flight searches in airports. I traveled before airplanes became boxcars of pressed humanity.

In the course of my job, I learned to respect those who saw the world through a different cultural lens. I visited prison wardens, assistants to emirs, and foreigners with custody of American children.

I can’t go back to those days again. By the end of my second tour in Saudi Arabia in the early 2000’s, I had to live by new restrictions on travel. We learned to be alert to the possibilities of terrorism, and not only in the Middle East. From the U.S. consulate in Dhahran, we watched on television as the twin towers fell on September 11, 2001.

Fortunately, I can conjure in novels the lessons I gained during the earlier days. The novels dredge up insights, before so much fire and fury, that I am only beginning to understand.

Twenty-nine school children were killed in a bombing raid in Yemen on August 9

Twenty-nine school children were killed in a bombing raid in Yemen on August 9. Do we care?

In between our fascination with Trump’s latest tweets and discussions about who goes to the next Super Bowl, did we even notice the tragedy?

Probably nine out of ten Americans don’t know Yemen exists. Fewer don’t know that we sell aircraft and munitions to our ally Saudi Arabia who uses them to bomb people there.

A bloody war has raged for years in Yemen between one regime supported by Iran and one supported by Saudi Arabia and its ally, the United Arab Emirates. Mass starvation and bombings of school busses and wedding parties are part of the conflict.

Why are Saudi Arabia and Iran fighting? Because these two countries have been locked in a power struggle for years for control of the Middle East.

The two countries adhere to different interpretations of Islam, whose advocates have fought each other for well over a millennia.

Dan Simpson, a former U.S. diplomat, writes: “I don’t care what Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates may have done for President Donald J. Trump or Israel; this time what the Saudis are doing in Yemen is way beyond what the United States should tolerate.

“The two Sunni Muslim states have, first, added U.S. 9/ 11-vintage enemy al-Qaida to their and our allies in the war in Yemen, putting us and the terrorists who attacked us at home on the same side in the war against the Shiite Houthis there. The war in Yemen has basically nothing to do with us in any case. Second, the Saudis and their allies carried out yet another brutal air attack in Saada in the north of Yemen on Aug. 9 that killed among others at least 29 children in a school bus in a marketplace.” (“Dan Simpson: Beyond the pale in Yemen,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 14, 2018)

At the very least, we can keep the weapons we sell to Saudi Arabia from being used in the conflict. As Simpson says, “The war in Yemen has basically nothing to do with us in any case.”

Third Horseman of the Apocalypse

In the Christian Old Testament, seeking food for self and animals is often a part of the stories. Herdsmen like Abraham moved to find better pastures for their flocks. A famine in Israel sent Jacob and his large family fleeing into Egypt. Lack of rain in the time of the prophets led Elijah to a miraculous encounter with a poor widow.

Obviously, areas with less predictable rain, as in much of the Middle East and parts of Africa, are more likely to suffer famine than countries in temperate climates. Sometimes, however, famine is not caused by weather but by conflict.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, who follow each other in the book of Revelation in the Christian New Testament, are sometimes depicted as conquest, war, famine, and death. The third horseman, famine, is not the result of weather but of conquest and war. It is human caused.

This kind of famine is afflicting millions of people in the countries of South Sudan, Nigeria, Somalia, and Yemen. In Sudan, they flee power struggles, often over oil revenues or ethnic rivalries. In Nigeria, people flee terrorism. Somalia’s looming famine is partly a problem with lack of rain but is increased by struggles with the terrorist group, al-Shabab.

Yemen, a country in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula, suffers fallout from rivalry between Saudi Arabia and its arch enemy Iran. The two countries are supporting rival factions that are tearing the country apart. Terrorist groups also have made inroads, as they often do in areas of conflict.

Some relief is possible if food shipments can be unloaded in one of the ports. According to reports, Saudi Arabia has so far been unwilling to allow shipments to the people they are fighting.

The United States has supported Saudi Arabia in this struggle. If we are truly a compassionate nation, we will exert as much pressure as possible on Saudi Arabia not to use starvation as a weapon of war. Else, we will be collaborators in the resulting deaths.

Aware in Saudi Arabia, Clueless in America

In Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in 1992, those of us working at the U.S. consulate watched via television with Saudi citizens as Bill Clinton defeated George H. W. Bush for the presidency. Many U.S. embassies and consulates around the world provide space for local citizens to watch results of major U.S. elections.

The elder Bush, father of later President George W. Bush, was popular in Saudi Arabia, having led a coalition of countries to free neighboring Kuwait in 1991 after Iraq’s conquest of the country and threat to Saudi Arabia. Saudis were disappointed at George H.W. Bush’s defeat. At least one Saudi remarked that the world ought to get a vote in U.S. presidential elections since the U.S. plays an influential role in world affairs.

Citizens of many countries follow the progress of U.S. presidential elections. On the other hand, many Americans appear clueless about events in the rest of the world.

Presidential campaigns lack serious attention to foreign policy issues beyond shallow posturing. Foreign issues don’t play well in Peoria. Yet global events constantly surprise and challenge us, from Pearl Harbor to twenty-first century terrorist attacks.

After World War II, the United States was one of the few democratic nations with its economy intact. Sometimes with crass self interest and at other times with true sacrifice, we accepted leadership in encouraging a world of democracy and justice. We can opt out now if we choose, but leadership may fall to others without those values.

A Clash between Religions or between Religion and No Religion?

In the waning years of the twentieth century, a few years before the terrorist attacks of 9/ll, Samuel P. Huntington wrote a best seller, The Clash of Civilizations.

The Soviet Union had dissolved, and the Cold War was over. Americans reveled in the dawning digital age, freed, they believed, from fears of a global conflict. Huntington, a professor at Harvard University, did not share their optimism for the new age.

In the absence of cold war ideology, Huntington suggested, religion was becoming more important, not less. Secularization had disrupted communities and cultures. I saw this disruption in the Middle Eastern countries where I lived during the 1990’s. Oil wealth led to vast change in one, Saudi Arabia. A consumer society emerged in one generation from an isolated, desert kingdom, bringing in Westerners who got drunk and watched x-rated movies. Most of the 9/ll terrorists came from this shell-shocked nation.

Humans needed, Huntington said, “new sources of identity, new forms of stable community, and new sets of moral precepts to provide them with a sense of meaning and purpose. Religion . . . meets these needs.”

Are the clashes and terrorist attacks since the publication of Huntington’s book only a struggle between religions or do they stem more from a struggle between religion and no religion?

Western societies have assumed an upward progress toward secular utopias with high rates of material benefits. In an age of rapid change, ordinary men and women may yearn for purpose and meaning. Where do they find them?

October Is the Perfect Month and the Best Month to Marry, Too

The poet Robert Browning liked the month of April: “Oh, to be in England now that April ’s there . . .” James Russell Lowell suggested June: “And what is so rare as a day in June? Then, if ever, come perfect days . . .”

Personally, I love the tawny colors and chilly nights of October. It’s the birthday month for three members of my family. It’s also, this year, our 23rd wedding anniversary.

We fell in love in Saudi Arabia. I worked at the U.S. consulate in Jeddah, and Ben was a flight training manager for Saudi Arabian Airlines, headquartered in Jeddah. We met at a square dance, held on one of the foreign worker compounds.

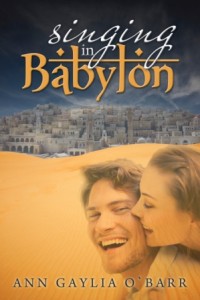

Our dates included square dances, hikes in the dessert, and shopping trips to the suq market. We sang Christmas carol in an expatriate home. Dating in a country which forbade an unmarried man and woman being together—anywhere— had its challenges. Some of those provided fodder for my novel, Singing in Babylon.

But when we decided to marry, no official Christian church existed in Saudi Arabia where we could plight our troth. (Contrary to popular myth, U.S. embassies and consulates are not authorized to perform marriages.)

So we flew to neighboring Bahrain, where Christian churches were allowed. The minister, an Egyptian Christian, performed our ceremony in the church, begun as a mission in the late 1800’s.

It seemed fitting for our international life.

A Concern Beyond American Idol

In my novel Singing in Babylon, the female protagonist, Kate, moves to Saudi Arabia from her native Tennessee to teach. She travels for her first time outside the United States. On a drive with her friend, Philip, an American journalist on assignment to the Middle East, she notices a veiled and gloved woman pushing a child on a swing in a public park. The woman glances at the unveiled Kate, and Kate wonders how the woman feels about this Western female’s intrusion into her world.

In my novel Singing in Babylon, the female protagonist, Kate, moves to Saudi Arabia from her native Tennessee to teach. She travels for her first time outside the United States. On a drive with her friend, Philip, an American journalist on assignment to the Middle East, she notices a veiled and gloved woman pushing a child on a swing in a public park. The woman glances at the unveiled Kate, and Kate wonders how the woman feels about this Western female’s intrusion into her world.

Later, she and Philip explore a seaside camp for Western expatriates on the shores of the Red Sea. She compares the women in bikinis with the veiled woman she saw earlier. For the first time, Kate understands the struggles of an ancient civilization to come to terms with the strange culture thrust into their lives by oil money.

Fast food restaurants, unveiled women, and automobiles bring unprecedented freedom and rapid change to a nation in one or two generations. These changes arrived in a country accustomed to centuries-old merchant towns, Bedouins herding camels and goats, and ancient tribes familiar with the customs of generations.

Fast food restaurants, unveiled women, and automobiles bring unprecedented freedom and rapid change to a nation in one or two generations. These changes arrived in a country accustomed to centuries-old merchant towns, Bedouins herding camels and goats, and ancient tribes familiar with the customs of generations.

Kate’s exposure to other cultures allows her further understanding of her own country, what is of value and what is neglected, and what directions it should take. Her experiences mature her perception of the world.

Travel to other countries is not the only path to an informed view. We have easier access to news reporting about world events today than at any time in the past. If we confine ourselves to the latest celebrity stories, however, and ignore the in-depth news, the advantage of this wealth of information will do us no good.

The unrest in the Middle East, for example, has a direct bearing on our future. The current brutality in Syria, where unarmed women and children were murdered this past weekend, and the unrest caused by Egyptian elections will affect us. When desperate millions thirst for security, they will choose whoever promises it: dictators, Islamists, or al-Qaeda.

Our response to such challenges will be wiser if we understand the problems. Ignorance and uninformed politics can lead to disastrous decisions.

Abiya or Bikini?

When I was assigned to work in Saudi Arabia, I thought I would wear an abiya, the black robe worn by most women there. It was the custom, I figured, and I would follow it.

When I was assigned to work in Saudi Arabia, I thought I would wear an abiya, the black robe worn by most women there. It was the custom, I figured, and I would follow it.

But once there, I decided not to wear it. It reminded me of the racial segregation that had been practiced in my own country. I dressed conservatively, long skirts and full outfits, but I didn’t generally don the abiya.

I was reminded of all this when I saw a recent cartoon of a woman in an abiya, making fun of the custom. For many in the western world, the abiyah or the burka is the symbol of male domination, of the discrimination against women, and of their lack of rights. I understand and generally agree, but I’m acquainted with another side of the story as well.

I knew a Saudi woman, educated in the U.S., who chose the old customs when she returned to her country. She indicated a disdain for much of what she had seen in the United States: the pornography, the broken homes, the casual sex. For reasons like these, some Middle Eastern and other women proudly don the abiya. For them, it is a symbol of the value they place on the family and the importance of a woman’s worth aside from her physical appearance. For them, it allows a focus on who they are and not on their worth as a sex object.

I knew a Saudi woman, educated in the U.S., who chose the old customs when she returned to her country. She indicated a disdain for much of what she had seen in the United States: the pornography, the broken homes, the casual sex. For reasons like these, some Middle Eastern and other women proudly don the abiya. For them, it is a symbol of the value they place on the family and the importance of a woman’s worth aside from her physical appearance. For them, it allows a focus on who they are and not on their worth as a sex object.

We are certainly correct to push for women’s rights, but is a woman in an abiyah any more to be pitied than a woman who chooses outfits only for their sexiness, as though her physical attributes are her only value?

Not Your Grandmother’s Oil Industry

The United States government soon will decide whether to authorize or reject an oil pipeline to bring oil from the oil sands of western Canada across the middle of the U.S. to Texas refineries.

Proponents say the pipeline will create jobs, so needed in a down economy, as well as mitigate prices at the gas pump. Opponents, some of whom live along the pipeline’s path, point to last year’s Gulf oil spill and voice concerns of possible danger to the pollution of the aquifer from which many draw their drinking and irrigation water. Als0, what about degradation caused by the process itself in Canada?

When I lived in the oil rich regions of Saudi Arabia around Dhahran, the original well that started oil production in that country in the 1930’s still pumped. In the section of the U.S. consulate where I worked, old pictures hung on the walls of the men who began developing that early oil industry. Oil production in Saudi Arabia was begun by American companies, but control long ago passed to the Saudi government.

Today analysts debate whether the world has reached peak oil, the time when the highest production of oil is reached, after which production gradually declines until the finite resource is gone. Regardless, oil use is growing because the middle class is growing in nations like India and China. Their citizens are buying more automobiles and more machines as they enter the consumer age.

These countries compete with North America and Europe for oil and have money from growing economies to influence nations from the Middle East to Africa and South America. The fact that some of the nations they deal with practice human rights abuses seems to be less of a problem for them than it (occasionally) has been with us.

Something for Christians to mull over as we make our individual choices of what we will buy and how we will live.

The Strength of Tension

As an American Christian living in Saudi Arabia, I found clues to my own people.

As an American Christian living in Saudi Arabia, I found clues to my own people.

When we Western expatriates hiked in the desert, we met groups of Bedouin Arabs who welcomed us, women as well men. Often the women did not even cover their heads. In the cities, however, Saudi women not only wore black abiyah robes and head coverings, but often veiled their faces and wore gloves. They appeared to be more isolated than their rural counterparts. Apparently, modern city lifestyles challenged tradition. The more conservative practices indicated a reaction to such challenge.

In times of change, Christians, like everyone else, cling to what we have always known. When our beliefs are questioned, we become like ethnic immigrant communities. We draw in together for protection against a larger society that follows a different set of rules.

Yet we Christians need both those with new ideas and those who would teach us the wisdom found in our core beliefs. Conservatives need liberals to remind them of larger issues, of the need for Christians to clamor for social justice and of the awful price which rampant consumerism exacts. Liberals need conservatives to remind them that Christianity without a crucified and resurrected Christ may become little more than a political party or a social club.

It is the tension of opposite forces coming together, we are told, that gives the arch its strength.

Mourning Osama Bin Ladin

I mourn Osama Bin Ladin. Not his death but his life. He wanted to purify the religion, we are told, of his native Saudi Arabia. He thought ideas brought into his country by Western nations were corrupting it. What an awful path he took in his attempt to carry out what in itself could have led to serious discussion and change within his country.

He could have chosen persuasion and a vocation as a peaceful spiritual leader, something like Gandhi. He could have reasoned and debated to bring changes. He could have kept open his own life to spiritual growth and change and listened to others with different opinions.

Instead, like too many people who desire change, he thought he had the right to kill people to bring about those changes. He wasn’t able to understand the rights of others to choose or to understand that no man, however close to God he thinks he may be, is God.

Perhaps humility is the first choice of those who would change others.

Feminism—Islamic Style

Isobel Coleman, in an article in the Foreign Service Journal, writes about Islamic feminists. In countries like Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, these women attempt to show that a reasoned approach to their religion, Islam, can open up possibilities for women and girls in conservative Muslim-majority countries.

http://www.afsa.org/FSJ/0411/index.html#/28/

Sometimes these women shy away from the term “feminist” because of the cultural Western baggage such a label carries. Whereas Western feminists generally have ignored religion, Islamic feminists tend to use their religion. They bring to their religious leaders passages in Islam’s Quran and suggest new interpretations. They see their religious inheritance as an ally.

One wonders how different the “cultural wars” in our society would have been if those who have sought change (often needed change) in the past few decades had begun with our religious inheritance instead of discarding it.

They might have dwelt on Paul’s words in Galatians 3:28: “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.” (NRSV) For starters.