Religious orders in the Middle Ages developed efficient methods of work in order to toil less and enjoy more leisure for prayers and other religious activities. As Europe entered the modern era, people began taking their surplus in goods rather than leisure. (Man, Energy, Society by Earl Cook.)

In prior generations, survival taught its own lessons: work efficiently, be frugal, or starve. After World War II, Americans found themselves in a golden age of plenty. One wage earner could support four or more people with a forty-hour work week. One could survive even though working less than ever before.

Americans, knowingly or not, faced a choice. We could work less and allow more time for other pursuits: family, religious activity, creative pursuits, community work, more education. Fathers could spend more time with their families, allowing mothers to explore outside career interests if they chose. Singles could work part time and obtain more education or pursue creative work that didn’t pay as well, if their talents led them there. Twenty-hour per week jobs might become the norm.

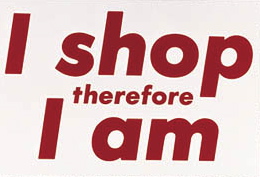

Or Americans could continue to work as they had and buy more and more things. Once “things” became the goal of work, however, the desire for more and more material goods required greater commitment to job and career.

Or Americans could continue to work as they had and buy more and more things. Once “things” became the goal of work, however, the desire for more and more material goods required greater commitment to job and career.

To overcome consumerism, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. believed that “we must rapidly begin to shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society.” By living “deliberately”—as Henry David Thoreau understood—we spend less, work less and enjoy life more.

We now are rich in things (or were before the Great Recession) and poor toward God, friends, families, communities, and our inner lives. To choose a Biblical metaphor, we worked the fields seven days a week, skipping our Sabbath days of rest. Now we find an enforced rest in unemployment and under employment.

The United States is one of the world’s oldest democratic republics, but democracy as practiced here is very much a work in progress. Its continuance is not guaranteed. Politics and power weave uneasily through our relatively new experiment in democracy.

The United States is one of the world’s oldest democratic republics, but democracy as practiced here is very much a work in progress. Its continuance is not guaranteed. Politics and power weave uneasily through our relatively new experiment in democracy. Benjamin Franklin is said to have remarked at the signing of the Declaration of Independence: “Gentleman, we must all hang together or, assuredly, we shall hang separately.”

Benjamin Franklin is said to have remarked at the signing of the Declaration of Independence: “Gentleman, we must all hang together or, assuredly, we shall hang separately.”