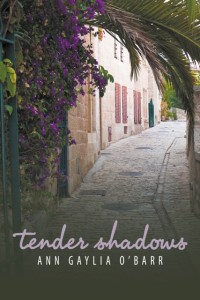

After working with a story over a long period, I develop an attachment to my characters. That’s probably why they reappear in later novels, often in cameo roles. Joe Harlan, an older Foreign Service officer, appears off and on as a kind of mentor to the younger characters. I finally made him a main character in Tender Shadows.

The author Wendell Berry, in his series of writings about the fictional town of Port William, Kentucky, does much the same thing. Main actors in one novel become supporting actors in another.

His novels, like mine, are not a connected series featuring one main character.

After completing Tender Shadows, I began a story about Mark Pacer, a transplant from Mocking Bird, Georgia, to the Foreign Service in 1976. I decided to let Mark have his own series (Where I Belong). A series lets me enjoy Mark from youth to—who knows—old age?

Following Mark’s life through the years also allows me to indulge my love of near history. The seventy years from 1945 (the end of World War II) carried us from early television to smart phones, from daily print newspapers with occasional extra editions to news from the far corners of the globe at the flick of an iPad.

What did this warp speed journey do to us? How does a fairly conservative young man, raised in an Appalachian village in the fifties and sixties, react to the changes of the seventies and beyond? Where does he belong? Will he become a refugee from the past?

Mark is twenty-one when the series begins, just finishing college and accepting an appointment with the U.S. Foreign Service. His father objects. “Too dandified for people like us,” he says, and we’re off into the story, which I’ve almost finished.

Tender Shadows happens within the first decade of the twenty-first century. Places of action include London; Washington, D.C.; Memphis, Tennessee; and a Persian Gulf emirate. Global terrorism changed habits, from the way we pass through airports to how we think about religion. The digital revolution sped new ideas around the globe, sometimes to those not ready for them.

Tender Shadows happens within the first decade of the twenty-first century. Places of action include London; Washington, D.C.; Memphis, Tennessee; and a Persian Gulf emirate. Global terrorism changed habits, from the way we pass through airports to how we think about religion. The digital revolution sped new ideas around the globe, sometimes to those not ready for them. I have difficulty pinpointing where the ideas for my stories come from. A Sense of Mission, my favorite, is the only one written in first person.

I have difficulty pinpointing where the ideas for my stories come from. A Sense of Mission, my favorite, is the only one written in first person. One of my novels (Quiet Deception) is set in a small college town and is my only straight mystery. The others contain a twist of mystery, but I’m more interested in how the characters evolve and the moral dilemmas they face.

One of my novels (Quiet Deception) is set in a small college town and is my only straight mystery. The others contain a twist of mystery, but I’m more interested in how the characters evolve and the moral dilemmas they face.

The characters in Tender Shadows differ in background and purpose and choices. They mirror society in the early twenty-first century. They include the digitally adept and the digitally challenged, the athletic and those who struggle to keep off extra pounds, the confident and the searchers.

The characters in Tender Shadows differ in background and purpose and choices. They mirror society in the early twenty-first century. They include the digitally adept and the digitally challenged, the athletic and those who struggle to keep off extra pounds, the confident and the searchers. The fancy name for coming-of-age stories is Bildungsroman (loosely translated: growth novel). This word is featured in a column by Christine Chaney, a professor of English at Seattle Pacific University, in the 2014 spring issue of Response (SPU) magazine.

The fancy name for coming-of-age stories is Bildungsroman (loosely translated: growth novel). This word is featured in a column by Christine Chaney, a professor of English at Seattle Pacific University, in the 2014 spring issue of Response (SPU) magazine. In grappling with the place of the mind, that is the use of the mind, in the Christian pursuit, I read a book written by Mark Noll, now history professor at the University of Notre Dame. His book, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, was first published in 1994. He sets out a challenge for evangelical Christians in the use of the mind. He describes the evangelical life of the mind as: ” . . . to think within a specifically Christian framework—across the whole spectrum of modern learning, including economics and political science, literary criticism and imaginative writing, historical inquiry and philosophical studies, linguistics and the history of science, social theory and the arts.”

In grappling with the place of the mind, that is the use of the mind, in the Christian pursuit, I read a book written by Mark Noll, now history professor at the University of Notre Dame. His book, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, was first published in 1994. He sets out a challenge for evangelical Christians in the use of the mind. He describes the evangelical life of the mind as: ” . . . to think within a specifically Christian framework—across the whole spectrum of modern learning, including economics and political science, literary criticism and imaginative writing, historical inquiry and philosophical studies, linguistics and the history of science, social theory and the arts.”